Note to my readers: This is an essay, not a regular update. A little bit personal (raw), as Lindsay Lohan would say.

“Maybe a reason a lot of people like or connect with my stuff is because, on a basic level, as human beings, everyone feels that loneliness as an outsider. May it be at school, at home or the society, you feel lonely sometimes, or you are not the same as everyone else, or you don’t belong. That sort of feeling comes out strongly in my music, no matter what language. Maybe that’s one way people can connect with my music.”

– Utada Hikaru, February 2009

Music, like anything else that arouses the senses, is inextricably tied to memory.

At the time that Utada Hikaru‘s Exodus was first released back in October of ’04, I was just coming into my own as a sophomore in high school. And by ‘coming into my own,’ I mean slowly embracing the fact that I was hungrily gawking at the boys in gym class far, far more often than I was at the girls, which was approximately never.

Granted, the fact that I was gay didn’t come as much of a surprise. My mother once had to be called into my preschool because I kept kissing the boys in class, and it was “becoming a problem.” Yet coming to terms with one’s own different-ness at exactly the worst time in anyone’s life to be different is no easy feat. Just ask Lady Gaga.

Exodus–along with Britney’s In The Zone a year prior (more on that for another time)–was my refuge.

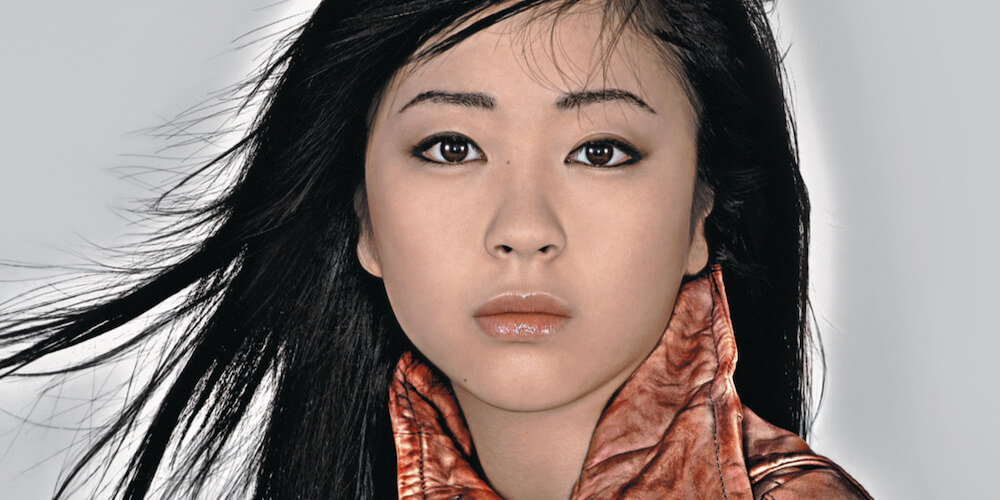

Utada Hikaru is a Japanese pop star, but not conventionally so: She doesn’t wear brightly colored frilly dresses adorned with bows, nor does she do choreography, nor does she perform twee cyborg electro-pop like the flash-in-the-pan J-Pop idols that come and go weekly on Japan’s Oricon Charts. (Not to say that she isn’t adorable in her own right, but she’s never behaved like a permanently stunted 12-year-old as many J-Pop stars so often do.)

She’s more of a singer-songwriter than a pop star, exclusively responsible for penning (and frequently, producing) all of her music, which is heavily influenced by early ’90’s R&B. “I’m not so much of a show-type of person, than I am more of a musician-type person,” she told the Seattle Times in 2010.

With her wry and nerdy sense of humor, poignant (and often depressing) lyricism, and intensely private lifestyle, Utada is essentially the Anti-J-Pop Queen, which is perhaps what makes her insane popularity in Japan all the more shocking: She’s sold over 52 million records, had over a dozen chart-topping hit singles, and 3 of her 5 albums are the top selling albums in Japan of all time, including First Love–the best-selling album in Japanese history.

I discovered Utada roughly 6 months prior to the release of her English debut, thanks to an Internet crush at the time. (I believe his name was something whimsical like Forrest, which only added to the appeal.) He was obsessed with Japanese music; something I’d always wanted to explore, but never really knew how to broach–aside from the occasional Dance Dance Revolution soundtrack offering.

Every week, he’d send me a new track to discover from artists I’d never encountered and later grew to adore, including Ayumi Hamasaki and BoA, resulting in dozens of CDs imported from Japan and Korea, OBI strips that littered my bedroom floor and enrollment at Brandeis University as a Japanese major. (This did not last.)

But there was one artist that I connected with far beyond the others.

I’d heard of Utada Hikaru already from the Kingdom Hearts soundtrack because of “Simple And Clean” (what high-school aged boy hadn’t?), but it wasn’t until my e-crush sent me the Japanese version of the song—“Hikari”—as well as bits and pieces of her last album Deep River, that I began truly falling in love with her work, and even more, her words (even if a translation never fully serves a song justice.)

It was the evocative, poetic nature of her music–a blend of traditional Japanese motifs with thoroughly modern complications in songs like “COLORS” and “Sakura Drops” that separated Utada in my mind as a huge inspiration.

And it wasn’t just the lyrics. There was something about Utada’s voice–the urgency, the way it quivered and broke as she reached her falsetto–with which I immediately connected. The same could not be said for my mother, who would cringe and immediately eject whatever CD I’d put into the car player immediately. “Ugh,” she’d scoff, disgusted. “Her voice is just so shrill! How can you even listen to that?” As a result, I listened on my own time.

Three albums after her record-shattering Japanese debut in 1999, Utada decided to set her sights on America.

The result was a potpourri of electronica, Top 40 synth-pop, jagged rock riffs, J-Pop melodies and pulsating dance beats. “My first English album was a very experimental, mad-scientist-in-the-laboratory kind of album,” Utada told Billboard while promoting her second English-language album in 2009. While she was beginning to touch upon these sounds with her last Japanese studio album–the gritty guitars of “嘘みたいな I Love You” the harpsichord-infused “Tokyo Nights”–the production was an entirely new beast.

With Exodus, the reigns were dropped: The album was largely recorded and produced by Utada alone in the U.S., mixing beats and recording vocals in solitude. “I had the time of my life, but it was a very intense, introverted process,” she told PopDirt. It was a time for Utada to explore and push her own boundaries artistically, making bolder decisions about beats and lyrics than ever before. “You don’t have to be Moby to use machines,” she told Teen People back in October of 2004, “There aren’t enough girls who [produce].”

Exodus, by and large, a meditation on alienation. For me, the stories being conveyed resonated deeply at the time. And while nothing within the album deals explicitly with being gay, there are countless moments that seem to channel the frustration, shame and loneliness involved in the coming out process and beyond.

On top of the dark pulsations of “Devil Inside,” Utada sings of a certain something burning within, which sounds as equally sinister as it does shameful: “Everybody wants me to be their angel, everybody wants something they can cradle/They don’t know I burn,” she sings, “Maybe there’s a devil, or something like it inside of me.”

I apparently wasn’t the only one who drew a connection: As I tuned in for the opening episode of the final season of Showtime’s Queer as Folk in May of 2005, I was stunned to find “Devil Inside” booming back at me over the speakers in the show’s opening club scene.

With “You Make Me Want To Be A Man,” a futuristic J-Pop-infused creation inspired by arguments with her husband (which foreshadowed their eventual divorce in 2009), Utada grasps for a way to communicate with her partner. “It’s very simple, it’s all about wanting to become another person and see it from another point of view,” she told FemaleFirst in 2005. Beneath the surface though, the song’s frustration-filled chorus seemed to threaten to spill a deeper secret, something that I wouldn’t do for at least a year later: “I really wanna tell you something/This is just the way I am/I really wanna tell you something, but I can’t/You make me want to be a man!”

Later on during “Animato,” the only song Utada personally translated in the liner notes of the Japanese edition so that her words weren’t misconstrued, she cries out for love ambiguously above dooming beats (“I need someone who’s true/Someone who does the laundry too/So what you gonna do?”) before spiraling into a chant. “DVD’s of Elvis Presley/BBC Sessions of Led Zeppelin/Singing along to F. Mercury/Wishing he was still performing,” the notoriously private songstress repeats, as if taking inventory of all her interests while diving into her own world.

I wasn’t much of an extrovert at the time, either.

It wasn’t because I was bullied much more than anyone else. Of course, there was the inevitable “faggot” that pierced the air any time I sat down at the all girls table during lunch, later hurled at me from a bus rolling by on the day of my senior prom while standing on the lawn next to my mother. And there were those swastikas that showed up in my notebook at one point. But for the most part, I managed to avoid heavier fire. I’m grateful for that.

Yet there was a darker period of my life when I wouldn’t leave my own room, largely because I was making more connections with the music I was downloading than with the kids down the street (and probably also a little because of a game called Everquest, which we’re not going to talk about now, or ever.) And although my own brand of lyrics would look a bit different than Utada’s–replace “Freddie Mercury” and “Led Zeppelin” with “Britney” and “Kylie,” perhaps?–everything about “Animato” and its private intensity spoke to me on a personal level (and still does.)

The most resounding moment of self-struggle comes within “Kremlin Dusk,” the album’s most masterful moment, and perhaps the boldest song Utada’s ever crafted–a grand opus of crashing drums, blistering howls and some of the most brilliant, thought-provoking lyricism she’s ever scribed. In short, it’s nothing short of a 5-minute pop revolution.

“All along, I was searching for my Lenore, in the words of Mr. Edgar Allen Poe/Now I’m sober and Nevermore, will the raven come to bother me at home,” she starts mournfully above the ambient, spacey sounds in the distance. (It’s no coincidence that Utada draws from Poe in the introduction of “Kremlin Dusk”–the two share the same birthday, and she’s cited his work as an influence in the past.)

The song’s structure is a stunning achievement in experimental pop, from its sweeping vocal runs (“Ho-o-o-o-o-o-me!”) and demented harpsichord, to the explosive guitar and crashing drum breaks provided by Mars Volta drummer, Jon Theodore. The song was like nothing I’d ever heard before (and even now, it remains defiantly ahead of its time)–the sonic embodiment of inner turmoil.

“Born in a war of opposite attraction/It isn’t, or is it a natural conception?/Torn by the arms in opposite directions/It isn’t, or is it a Modernist reaction?” Utada angrily cries. It was that one line that caught me off-guard immediately. “Opposite attraction”? “Natural conception”?

To me, the line spoke to a battle brewing inside. I remember clinging onto those words, tracing them into the margins of my notebooks at school as I sought to provide that answer for myself–or at least to remind me that I wasn’t the only one.

One of the greatest live performances I’ve ever witnessed in my life. No hyperbole–just fact.

Not everything on Exodus mirrored the intensity and anger of coming out. Sometimes, it just captured the awkward.

Songs like “Let Me Give You My Love” found the singer suddenly flirting with the verge of obscene, Britney style, indulging in heavy moans and shocking her more modest-minded Japanese audience with eek-worthy, playful come-ons: “Can you and I start mixing gene pools?/Eastern, Western people, get naughty/Multilingual,” she teases. “I found with English, I could venture into that more. I could be dark or intangible in some places or be very humorous. And still it just all came together well, so that was very fun to do,” she told Asiance.

“The Workout” is an infinitely more bizarre experience: Between its tongue-twister lyrics (she rhymes “Amen” with “Tomb of Tutankhamen” at one point) and disjointed booty-bounce beats with all the grace of a baby giraffe learning to walk, nothing on the album plays quite as strangely–or less seductive. “I think I was trying to be more mature than I really was, I mean, what was I, like, 19 or 20, and some of the stuff I was trying to be an adult, I was trying to say, I can do this. I’m grown-up, but I was a kid, kind of,” she admitted to JETAANY Magazine years later.

That song will forever be tied to the memory of my first boyfriend, who came into my life a month after the album was released. He was tall, British and doofy, with a mischievous smile and a slight lisp that prevented him from being able to pronounce my name correctly (“Bwadley”). We met through my best friend Amanda, one of the select few who knew that I was gay at the time. She knew Ben from an after-school theater program and thought he’d be a match. And by match, I believe the general thinking was: “He’s gay too. It’s perfect!”

Since Ben and I went to different schools across town (oceans apart, really), we kept a journal between ourselves, passed along through our middlewoman Amanda who, undoubtedly, read each entry on the bus ride in between. It makes for a humiliating read now: Over-the-top love letters between two people who’d known each for less than a month, quotes from Utada, Britney and, more worryingly, Joss Stone, playing cards of naked men, magazine clippings of Madonna, and his vaguely manic crayon drawings and worryingly grim poetry.

I had no idea what love was, and I certainly didn’t feel it for him, but I tried my best to act like I did in those pages.

Each weekend, we’d get together in secret at my best friend’s house. I’d play an album for both of them while we sat and made anxious small talk, and then we’d watch a movie together. I remember introducing him to Exodus for the first time, nervously sitting up against the wall next to him on my best friend’s bed. That day, conveniently, she had left the room to take a shower. As we awkwardly held hands and smiled, “The Workout” came moaning into the speakers, and the two of us soon launched into what would be my first full-on make out session.

I still vividly remember the feeling of moving way too fast as Utada awkwardly groaned her way through the song—a blend of horniness, guilt and vulnerability (“Pull it up, push it down…”). We kept going. Shirts came off. He quickly unbuttoned my pants, kissed down to my stomach, and then started to go down further (“Up and down, ‘til your knees start shakin’, shakin’…”). Within minutes, it was over. I felt gross and ashamed. The memory attached to the song was so strong that I couldn’t hear it for nearly a year afterward without a tight, uncomfortable knot forming deep in the pit of my stomach. We lasted for one month.

Even now, I can’t help but wince just a little when the song plays. (I’m still sorry it happened in your bed, Amanda.)

Apart from the personal flourishes throughout Exodus, Utada also stretches herself as a storyteller while still, unconsciously or otherwise, continuing to explore the album’s theme of outsider-dom.

My personal favorite, “Hotel Lobby,” bounces along a sprightly synth-pop beat with all the cheerfulness of a hit J-Pop record, yet weaves an unexpectedly dark narrative of a prostitute’s daily dealings in a hotel. “She goes out unprotected/She doesn’t listen to her best friend/It’s only for the money, for the money.” As the sad tale slowly unravels, the song’s chilling chorus fills in the blanks: “Watch me as I walk in slowly/When your eyes meet mine, it’s in the mirrors of the hotel lobby,” she croons, her voice drifting as a lonely echo in the distance.

I’ve never had a life experience even remotely comparable to that of “Hotel Lobby.” Nor do I intend to. Still, there’s something oddly haunting about the production; a ghost lurking in the hotel mirrors in between the gleeful beats. “She’s unprotected, she’s unprotected,” Utada cautions. Fear of risk, disease and loneliness flooded my mind often.

At my lowest, “Hotel Lobby” was the one song that I found solace in most often, usually while sitting alone in the dark.

In places, Exodus wasn’t even necessarily about conveying an emotion–it was simply an exercise in letting go.

While the album was largely produced by Utada herself, the singer enlisted another producer to help craft some of the tracks: Timbaland. Just on the brink of his second resurgence on U.S. radio (the first being with Aaliyah and Missy Elliott back in the late ’90’s, the next being in 2006 with Justin Timberlake and Nelly Furtado), the iconic R&B producer helped to produce two tracks: “Exodus ’04” and “Let Me Give You My Love.”

The collaboration proved trying at first: According to an interview with Utada in The Washington Post, the artists butted heads: “I told him, ‘I have to write my own stuff,’ Utada says. “And he was like, ‘What do you mean? I have my own way of doing stuff.’ And I was like, ‘I have my own way of doing stuff, too.’ It was just a matter of getting to know each other.”

Still, it paid off: “Exodus ’04” is a sublime pop record about moving forward and navigating new territory, gliding across one of Timbaland’s signature tripping Bollywood-esque samples and a cool ripple of piano: “Daddy, don’t be mad that I’m leaving/Please let me worry about me/Mama, don’t you worry about me/This is my story,” she sings.

Two years later in August of 2006, I found myself in the backseat of my father’s car heading up to school in Boston, squished up against bedding, one too many first aid kits and more posters of pop princesses than school supplies, with my entire family dispersed somewhere in between. I listened to “Exodus ’04” on repeat in my headphones as I quietly cried and glanced out the window, finding solace in Utada’s words when nothing or no one could possibly calm me down. “We’ll say goodbye to the friends we know, this is our exodus…”

Granted, Boston was only just 2 hours away from home, but for a boy who had yet to make it through the night at every sleepover in his life without darting to the nearest phone and demanding to be picked up by midnight, it was no minor undertaking.

It’s been exactly 8 years since Exodus was released, and listening to the record now is an entirely new experience.

As the distance grows between then and now–a life spent away at college, a nearly 5-year relationship with my first (and still, only) true love built, blossomed and broken apart in between (our song was Utada’s “Passion”–notice a pattern?)–the album plays less like the journey of self-discovery it once did, and more like an audio recording of a conversation from years ago. There’s a lingering nostalgia now that drifts in between the string samples of “Exodus ’04” and in the fragility of Utada’s voice as she quivers the word “home” in “Kremlin Dusk.”

It’s an indelible part of Utada’s music.

When I listen, I still think of Utada sitting up late at night alone, toiling away and threading samples lent from Timbaland’s studio against her own self-crafted drum patterns while quietly humming melodies into a microphone, crafting her imperfect masterpiece. The solitude comes through in the songs, lyrically and sonically.

I’ve been brought up in the digital age; a time that promises to bridge the gap between cultures and expand the global village. Yet we’re at our loneliest yet, incapable of holding conversations in person, spending more of our time in isolation–even marrying pillows instead of people.

A few months ago, I found myself sitting in the lobby of a posh hotel in downtown Boston, where I was staying for a weekend to visit friends from college. As I sat watching the incoming patrons come and go, waltzing in and out of elevators with their oversized designer luggage and puffy winter jackets, I was consumed by an immense sense of sadness. I was about to meet a longtime friend in no more than 3 minutes, but it was unshakable. Nothing felt genuine. Everything felt empty. Not knowing how else to occupy my time, I took out my phone, snapped a picture of the lobby and sent it out online with a fitting caption: “Meet me in the hotel lobby, everybody’s looking lonely…”

To my surprise, a flood of people began responding instantly–with gleeful nostalgia, lyrics from Exodus, and urgent pleas for Utada to return from her hiatus. In that moment, I no longer felt alone.

“Hey!” I heard off in the distance. I looked up, lowered my phone and smiled as she glided through the revolving door.

Exodus was released on September 8, 2004. (iTunes)

EDIT: A few days later, Utada herself tweeted about this article.

Thanx @MuuMuse for a lovely article and some insight into the reason behind the high gay count of my fan populace :) http://t.co/LG4MiVOR

— 宇多田ヒカル (@utadahikaru) September 2, 2012