Everyone’s got something to say about Lana Del Rey.

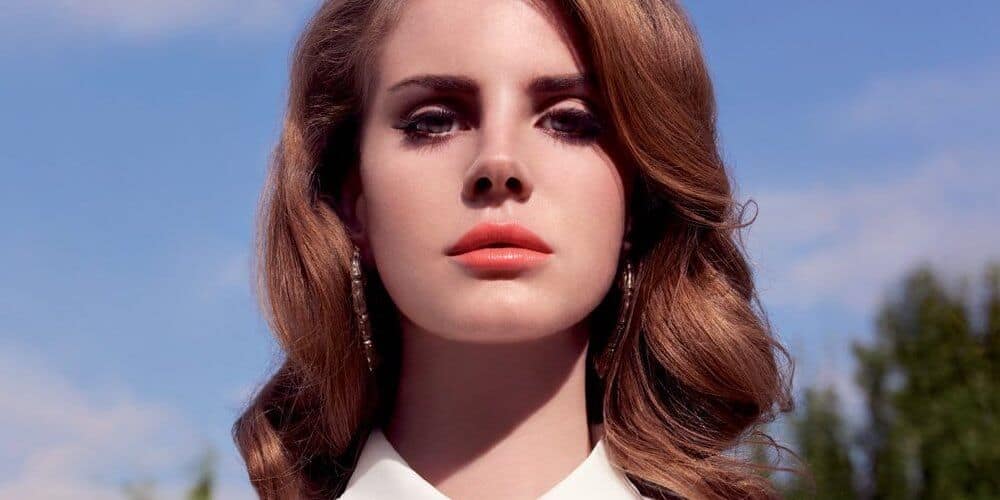

In Late June, the cut-and-paste clip for the singer’s “Video Games”–then just a buzz track–dropped with a thud onto YouTube. Spliced between old movie sequences, paparazzi clips and fuzzy home videos, we watched as a husky-voiced, otherworldly chanteuse pouted and cooed a dreary, vintage-sounding ode to her beloved: “It’s you, it’s you/It’s all for you, everything I do,” she begs. The song’s haunting melody, coupled with Del Rey’s bombshell looks and curious mannerisms, drew adoration and anticipation from countless bloggers worldwide, including myself.

Only weeks after the clip premiered, the overnight Internet sensation came under fire, as dissenters were quick to point out what Google already knew for months: Lana Del Rey, born Lizzy Grant, was raised by her father, a real-estate entrepreneur, and her mother, an advertising account executive in Lake Placid. After a stalled launch two years prior, the singer had since been signed to Interscope in March of 2011, paired off with top UK writers and hip-hop producers, and thrust quietly into the world (again) as Lana Del Rey.

Critics scoffed at her stories in interviews of living in a trailer park (despite this fairly telling interview from back in 2008 in…a trailer park), as though an artist’s legitimacy is earned only by being born into hardship. Her image changed, too, including an unquestionably fuller set of lips (“They’re fake!”, they cried), as though the emotional value of a song is determined by a single Restylane injection.

In short, haters continued to hate: Internet campaigns–spearheaded by the ever-sarcastic Hipster Runoff–effectively began a Del Rey witch hunt, tearing apart her music lyric by lyric, her videos frame by frame, and over-analyzing every word she’s ever uttered in an interview to an obsessive degree.

It didn’t help that Del Rey’s star skyrocketed too quickly: When the singer took to the stage of Saturday Night Live in early January for a jittery performance of her double A-side debut, the world–largely unaware of her particular brand of deep-voiced, slow-spoken artistry to begin with–pounced: ABC news anchors, musicians and all began eagerly participating in the most bizarrely overwrought public skewering, labeling it “the worst performance in SNL history.” (It wasn’t.)

To this day, the persecution continues with sexist headlines (“Lana Del Rey shows off some upskirt on some magazine cover!”) and nasty blog comments, as Indie absolutists hungrily seek any opportunity to “out” Del Rey with a quivering, condemning point of the finger shouting “FRAUD!”

In reaction to a recent interview in which Del Rey discussed drinking underage to deal with her own troubles, Hipster Runoff posted a mocking meme of Del Rey, the words “My daddy only cared about hoarding dot-coms: Confessions of a Teen Drinker” written across the picture.

If there were ever a case to be made about cyber-bullying, Lana Del Rey’s e-burning at the stake would be the shining example.

It’s like I told you, honey…

Early into the campaign, Del Rey’s management described her sound as “gangsta Nancy Sinatra”–a term she personally disapproves of, despite the fact that it remains the most astute characterization of Born To Die: It’s as though Sinatra’s “Bang, Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down),” in all of its swagger and seriousness, were stretched across a tripping hip-hop beat for 15 tracks. The result is a blend of youthful nostalgia and noir, capturing the very essence of summertime sadness (which, conveniently enough, is one of the song titles) on a tear-stained Polaroid from a summer decades ago. Sound a little melodramatic? So does this album–and yet, it works.

Largely produced by hip-hop producer Emile Haynie (Kid Cudi), Born To Die is an incredibly cohesive effort, as each song on the record is characterized by recurring noises: Lonesome plucks of a surf guitar, a distant male yelp in the distance, cinematic strings. Along with Haynie, Del Rey worked with several other talented songwriters and producers, including Jeff Bhasker (Kanye West), Rick Nowels (Lykke Li) and Chris Braide (The Saturdays, Diana Vickers).

Although the tradition of storytelling continues to die a slow death in today’s pop music (unless tales of getting down in the club are considered storytelling–to that, we have a great surplus), Del Rey has crafted evocative, colorful narratives, relying on Americana symbolism and Old Hollywood glamour of yesteryear to tell her tales: Stories of wild love affairs, girls gone wild, reckless abandon, and partners in crime riding off into the sunset.

“Born To Die,” the album’s defining anthem, sees Del Rey riding out the rest of her days with her bad boy in tow. And even if it marches forward with all the heavy-heartedness of a funereal procession sonically, the song’s overarching ride-or-die outlook remains endlessly romantic: “Let me kiss you hard in the pouring rain/You like your girls insane/Choose your last words/This is the last time/’Cause you and I, we were born to die,” she declares.

“The concept of almost every song on the record is a dark love story seen through hopeful eyes,” Del Rey told Flush The Fashion almost a year before her debut was released. Throughout the record, Del Rey toes the line gently in between death and romance, happily swooning about love while hinting at something much murkier working underneath: “I’m feeling electric tonight/Cruising down the coast, goin’ ’bout 99,” Del Rey declares defiantly above the marching beat of “Summertime Sadness,” “Got my bad baby by my heavenly side/I know if I go, I’ll die happy tonight.”

On “National Anthem,” Lana revels underneath bursting fireworks with her man, painting an idyllic scene of Bugatti whips and mansions in the Hamptons. “He loves to romance ’em/Reckless abandon/Hold me for ransom/Upper echelon,” Del Rey dreamily purrs. It’s one of the album’s most evocative moments lyrically, as the songstress breathlessly indulges in the extravagance and grandeur of the American Dream, a la The Great Gatsby: “Money is the anthem/God, you’re so handsome,” Del Rey chants endlessly.

Tragically, the album version of the song–which trots along on a dark, spooky beat–utterly pales in comparison to the demo version that leaked weeks ago, which shines infinitely brighter above a gritty electric guitar and a punchier beat that pays proper justice to the kaleidoscopic grandeur of the song. It’s not that bad in the end–just a major missed opportunity.

When Lana’s heart isn’t being pumped full of delight, it’s crashing down in misery: One of the album’s standout moments, “Dark Paradise,” finds Lana mourning the loss of a love at sea: “There’s no remedy for memory/Your face is like a melody, it won’t leave my head,” Del Rey bellows out into the night. Yet beneath the song’s gothic exterior lies an deeply romantic sentiment, suggesting that love trumps all circumstances–even death: “No one compares to you/I’m scared that you won’t be waiting on the other side,” she confesses above the brooding beat.

Elsewhere, as on the bleak, slow-swaggering “Million Dollar Man”–another one of the album’s finest moments–Del Rey plays a broken-hearted songstress in a smoke-filled jazz bar, flexing her supreme songwriting skills alongside co-writer Chris Braide: “I don’t know how you get over, get over/Someone as dangerous, tainted and flawed as you,” Del Rey sorrowfully croons, her voice quivering with all the conviction of Fiona Apple at her finest.

“I heard that you like the bad girls honey, is that true?”

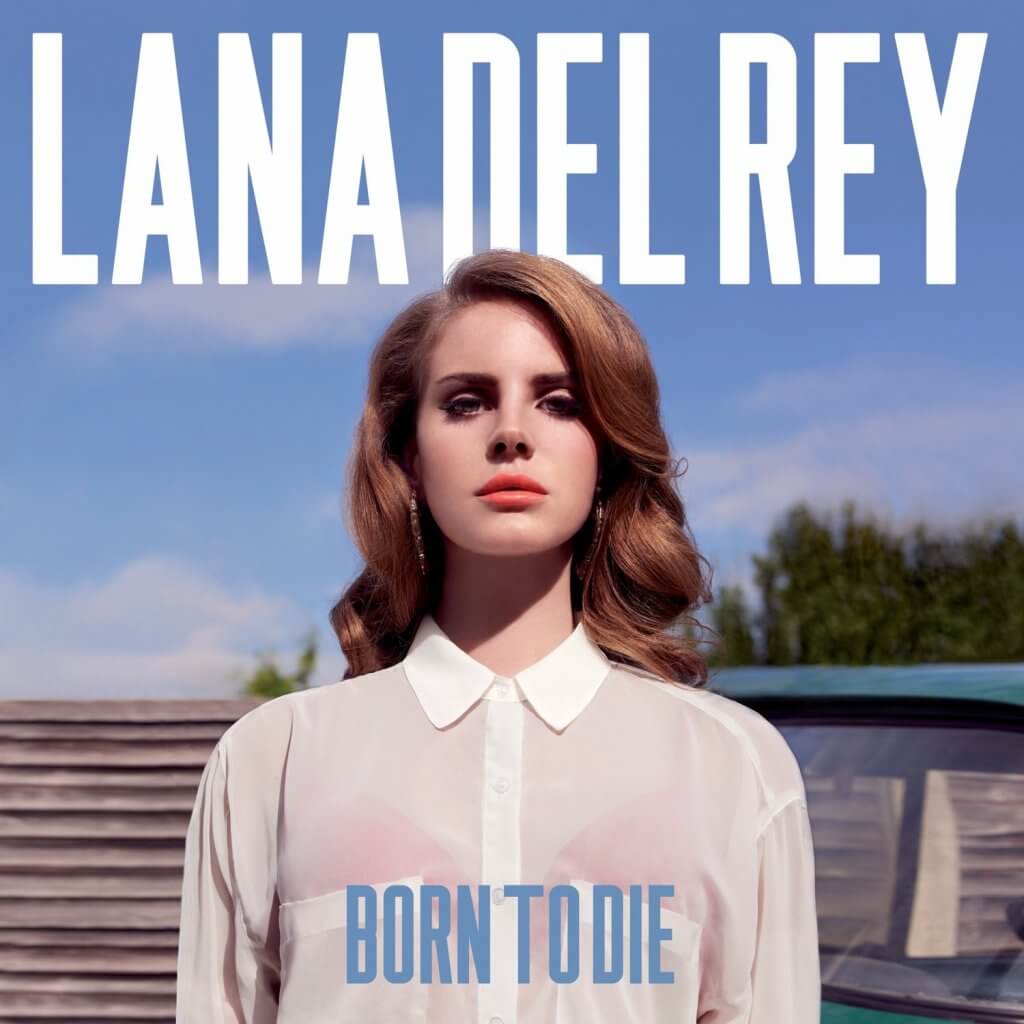

Being a bad girl certainly seems to be one of the most recurring themes in Born To Die: Look no further than the album cover itself, as a stony-faced Del Rey stands tall against the bright blue sky in a button-up white blouse, looking like a well-to-do Catholic school girl. It’s a perfectly stark photograph, sans one scandalous detail: That bright red bra visibly peeking out underneath the fabric.

When she’s not mournfully wailing on anthems like “Video Games” and “Born To Die,” Del Rey is getting downright flirty, promising sweetly-sung love affairs full of lavishness, laughter and so, so, so many kisses–in the pouring rain and otherwise.

“Off To The Races,” one of the tracks co-penned alongside Tim Larcombe (Girls Aloud, Sugababes) comes to life with vivid imagery and brag-like excess, as though Lana was putting the lyrics to a classic rap track to song: Bacardi chasers, glimmering swimming pools, bikini tops, red nail polish, gold coins, cocaine hearts. Except, of course, Lana Del Rey isn’t playing the boss: “I’m your little scarlet, starlet, singing in the garden/Kiss me on my open mouth,” Del Rey girlishly hiccups.

Indeed, Del Rey’s throwback persona dictates her lyrics in the most traditional sense, pitting the indie-pop princess with all the helplessness and unwavering loyalty of Tammy Wynette‘s “Stand By Your Man.”

During the anthemic “This Is What Makes Us Girls,” Lana and a group of trouble-making friends that play hard, love harder and raise Hell at sixteen years old: “We were skippin’ school and drinking on the job…with the boss,” Del Rey deadpans. It’s one of the album’s most instantly catchy cuts, even if the overarching message raises a feminist eyebrow raise or two: “This is what makes us girls, we don’t stick together ’cause we put our love first,” she croons. Erm…girl power?

At a point, the ‘I’ve been a bad girl, daddy’ shtick can prove somewhat troubling at times, especially as she navigates into territory like “Lolita,” in which Del Rey invokes her inner Betty Boop, raising her voice to a nearly childish high as she jumps from the bellowing of “Video Games” to coquettish tease: “I want my cake and I want to eat it too/I want to have fun and be in love with you,” she playfully teases.

Yet if we are to embrace Lana Del Rey as a “throwback,” we accept the outdated ideologies and notions about gender that come with the persona. There’s something very knowing–or perhaps just scandalously alluring, about Del Rey’s girlish teases throughout. True, there’s nothing too empowering about her music (I don’t think “Born To Die” will become the theme of the “It Gets Better” Movement any time soon), yet the neediness and fragility of songs like “Without You” are ultimately just as valid as any other emotion–even if they’re not particularly “good” kind.

Frankly, Born To Die is likely a more accurate depiction of our thoughts than some listeners would ever care to admit.

“Not even they can stop me now…”

With all the dialogue that Lana Del Rey has, intentionally or otherwise, generated–about authenticity, image, gender roles and everything in between, it’s difficult to fully appreciate this body of work at hand amidst both endless hate speech and intelligent, well-researched analysis (and yes, I’m self-aware enough to realize that I’m yet another voice in the mix).

It’s only when both the naysayers and Lana absolutists are reduced to a buzz in the background that the beauty in the darkness of Born To Die reveals itself: It’s a well-produced record–incredibly so, and even if the somewhat depressing, world-weary tone throughout the album weighs heavily (and a bit redundant) all in one go, Born To Die is still one of the most intriguing debut efforts in years.

In fact, not since Florence + The Machine‘s 2009 debut, Lungs, has there been such a masterful, well-crafted debut–nor with such a defining sound. Despite who or whatever she was prior to becoming Lana Del Rey, the rich, romantic stories and sweeping melodies that pour out each gorgeous track off of Born To Die will outlast any hateful headline that ever comes her way.

Born To Die was released on January 31. (iTunes)